Silent Witness (GER)

Silent Witness (GER)

by Cornelia Suhan

Couldn't load pickup availability

‘A war is not over when the weapons are silent.’ - Cornelia Suhan

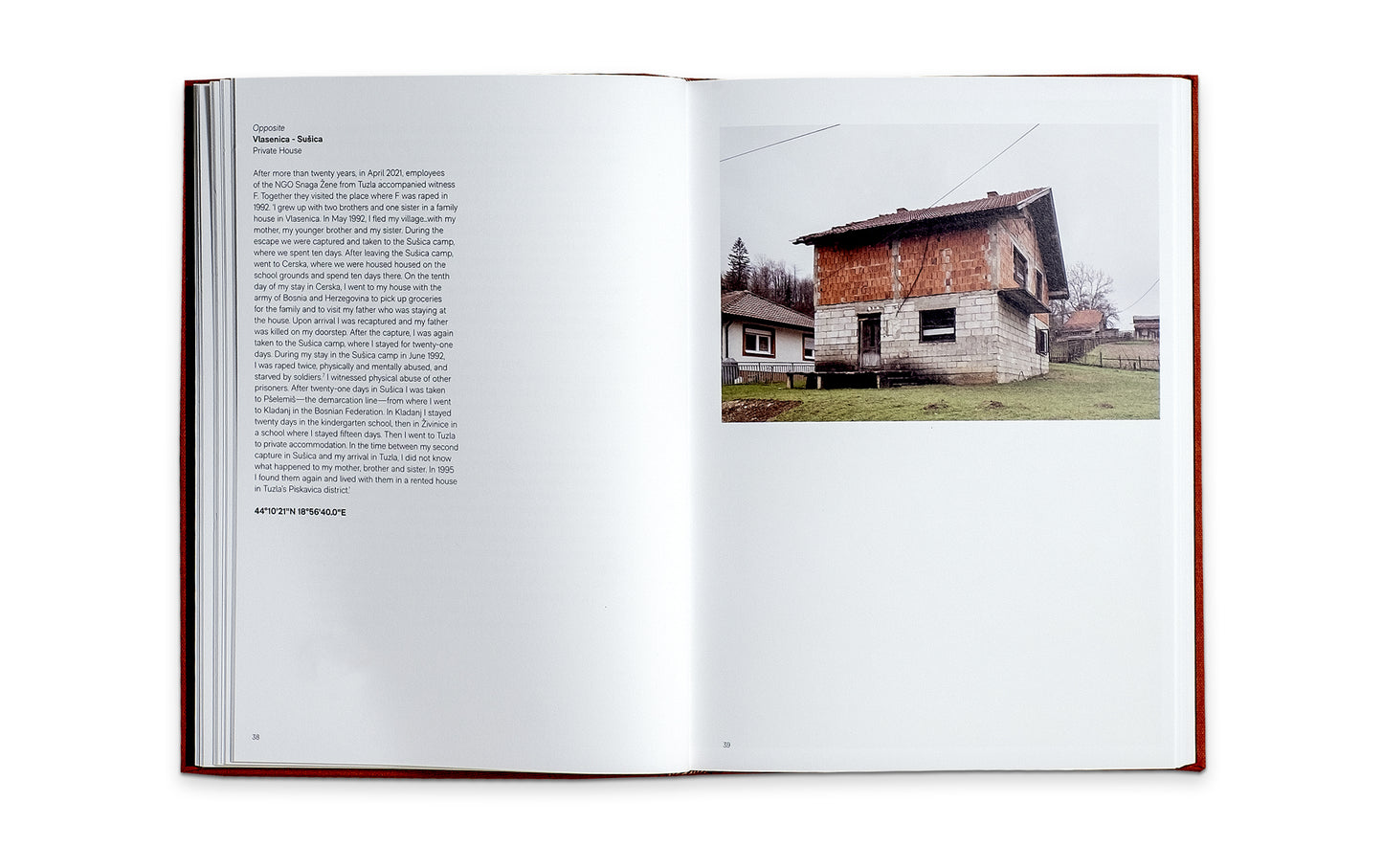

In Silent Witness photographs of private houses and public buildings in which war crimes—specifically rapes of women of all ethnic groups living in Bosnia and Herzegovina—were committed during the Bosnian War (1992-1995) are combined with testimonies from the women who survived. Cornelia Suhan’s photographs of these buildings— the silent witnesses—allow the stories to be told without exposing those affected to the public again.

More about this book

More about this book

PLEASE NOTE: This is a German language edition

Published March 2024

170 x 234mm protrait

192 pages, 89 images

Hardback

ISBN 978-1-915423-24-5

A donation of 20% of proceeds from sales or pre-orders of the book purchased directly from gostbooks.com will be donated to Vive Žene (https://www.vive-zene.de/)

German Photo Book Award 2024 Silver in Documentary Category

Share

In the press

From the author

-

-

- Cornelia Suhan